WE STAND at the petrol bowser, slumped but attentive, watching the screen count upwards. The number is awesome, in the sense of inspiring awe. Shock and awe. How can it be that high? How can they make counting machines that move that fast?

You expect people to shout out, to curse, yet there's a strange quiet on the petrol station forecourt. We're like penitents in some strange religious service. We pay up and limp off like beaten dogs.

People say the car will soon disappear - priced out of the reach of all but the rich. Yet it's tough work imagining life without the car. Around here, it's a part of life; a strange tumour wrapped around our essential organs.

For the past five decades, the car has been the ultimate symbol of escape - the tool that unshackled us from our parents. It has been the ticket to freedom. The badge of adulthood.

There are so many things we'll lose, once the car disappears. Like the peculiar smell of stale milk and squashed lollies that built up around a child's car seat.

Or the best route from Sydney to Brisbane. Or - in the dying days of petrol - how to get an extra kilometre to the litre by coasting down the hills, or removing your roof racks, or filling up on cold mornings when the petrol was less likely to vapourise before it went into the tank.

"Oh yeah, mate, I'd save 5, maybe 6, cents a week, just by filling up at the right time, in terms of the diurnal temperature range."

The family holiday will be the most obvious casualty of life without the car. A whole culture will be wiped out - the long trips up the coast, the Boxing Day traffic jams, the way all the parents were driven insane somewhere around Macksville by the 44th repeat of the Wiggles CD.

Perhaps people will keep the old traditions alive, much like enthusiasts recreate medieval battles. Unable to leave home due to high fuel costs, families will just re-enact the traditional holiday - the kids forced to sit on the lounge-room couch for six hours at a stretch, chanting "Are we there yet?" while the father threatens to "Stop this car this bloody minute unless everyone shuts up and lets me drive."

Dad will be saying this, of course, sitting on a kitchen chair, placed just in front of the couch, his hands on an imaginary steering wheel. The mother will sit next to him, pointing out the speed limit. Occasionally they'll throw a packet of chips into the back, keeping the kids quiet for another stretch of pretend highway.

Once the car is consigned to the dustbin of history, there will be a wave of nostalgia. Maybe Old Sydney Town can reopen as the Petroleum Museum and Display Village. Just need to work out how people will get there.

It will be a great place, all the same. We'll have a fake drive-in, people squeezed together in stationary cars and the sound coming through those little speakers hung from the window. The cars would be immoveable - long ago emptied of petrol - so you'd miss the pleasure of driving off with the speaker still attached.

And then there'll be the pop music hall of fame, with the Ted Mulry Gang singing Jump In My Car, and Aretha Franklin belting out Freeway Of Love.

People will nod, tap their feet in time and remember the good old days. Sure, what happened was inevitable; in the end the private car had to go. But then they'd shake their heads and lament the new generation of singers, no longer able to sing about that glorious and destructive beast, the private automobile.

Somehow that new track, Jump On My Bus, isn't nearly as funky.

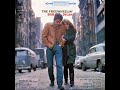

This is me in 1974 in my Sprite at the family home in Chatswood, Sydney.